Julian Costley, CEO & publisher at Bite-Sized Books, interviews some of our authors to provide further background to their books and to their approach to writing. And a little ‘behind-the-scenes’ glimpse of their life and influences.

In this edition Julian talks to author, playwright, screenwriter, journalist, columnist, biographer, lecturer and senior TV executive about his life, works and dealings with serial killer Charles Sobhraj the subject of the BBC/Netflix series, The Serpent.

JC

Delighted to be able to chat and include you in our venerable roster of authors in our Bite-Sized Books Meet Our Authors series.

Let’s start with your background and education. A life that started in the city of Poona India? A name that I’ve read was Anglicized to Poona in 1857 by the English during British rule. Which changed its name to Pune in 1978. What followed?

FD

I was born in the Western Indian city, which was then called Poona. Yes, its original name was Pune which was altered during the British Raj to suit English pronunciation. It reverted to that name in 1978.

I went to school and college in Poona, from the age of eight to nineteen. My father was an officer in the Indian army and was transferred from one military station to another every few years. My parents decided that I and my sister should stay with my maternal grandfather and two of my mother’s spinster sisters – our aunts – so that we didn’t change schools every two years. In fact, my father was posted to a ‘non-family’ station in remote Kashmir and there were no schools which we could have attended there.

Every holiday, three times a year perhaps, we went to our parents to spend the summer or winter months in Kanpur, Kashmir or wherever.

JC

And you’ve amassed quite a collection of degrees?

FD

I did my first degree, a B.Sc. in Physics from college in Poona. It was a University of Poona degree, and I used that to apply to Pembroke College Cambridge which gave me a place to study, for the first two years, Natural Sciences and then in my third year a Part-2 Tripos in English. Of course, in Cambridge you earn a BA and that turns automatically into an MA, so there I am, after three years at the university and two years thence, an MA (Cantab).

I went on, through sheer luck, to be offered a scholarship to do a thesis on Rudyard Kipling at Leicester University and graduated in the next two years with an MA from there.

Then after some years teaching in a London school, I took a sabbatical and went to York University and picked up a Diploma in Education…the honorary degrees, a couple, don’t really count!

JC

You’re a writer, playwright, screenwriter, but also a left-wing activist. In addition, a columnist, biographer, lecturer, and, to top it all, a former Commissioning Editor for Channel 4. How did it all come about?

FD

Being in the right place at the right time. I picked up my socialist views at a very young age in India as I observed two phenomena that were absolutely, overwhelmingly forced through passive observation on my mind. The first was the abject poverty all round me – starving people, natural disasters — famine and death… and the second was the, for me, stifling, irrational prevalence of shameful and pagan superstition.

My instinct connected the two – causally. I began to read the communist pamphlets sold on the pavements of Mumbai and Delhi. In Britain, though I came as a student and not as an ex-colonial worker in the mills, London transport or some other employment at the bottom of the working-class ladder, I experienced some acute racism. That was bound to drive me into radical politics and, successively, the membership of several organisations such as the Indian Workers’ Association in Leicester, then the Black Panther Movement in London, Teachers Action through my profession and then an active political collective called Race Today.

I began writing, at first journalism for a news agency and then fiction. Very much through luck and the admonition of the Trinidadian philosopher CLR James who came to a crowded meeting of the Black Panther Movement and told us that instead of devoting ourselves to the pages of our publication Freedom News, we should write interesting accounts of incidents at our places of work which would get the readers collectively identifying with us rather than being harangued with political opinions.

I saw the sense of it, and I began to write short anonymous accounts of episodes, events and petty crises at the school where I worked as a teacher. After perhaps more than twenty of these which appeared in Freedom News I was approached by a young man in a grey suit who called at the door of my school’s staffroom asking if I was Farrukh Dhondy.

I said, “Does he owe you money?” “No,” he said and went on to tell me he was from Macmillan Publishers and that he had read my anecdotes of incidents involving black kids at school and wanted to publish them as a book. His exact words were’ “An audience for multicultural literature exists, but the literature does not.” He proposed I fill the gap, and I said the pieces in Freedom News were journalistic and I could write actual short stories. He offered me a contract straight away.

That began my fiction writing career which has continued these past five decades with perhaps thirty books with my name as their writer.

The fiction led to stage directors and then the BBC approaching me to write plays, TV series and screenplays. Having done that successfully for a few years I was, though it came as a complete surprise, invited by Jeremy Isaacs, the then head of Channel 4, to replace their departing Commissioning Editor, Sue Woodford, who had become Lady Hollick and was off to the USA. Again, right time, right place. Luck.

JC

Your literary work is so extensive. As a publisher I’m intrigued that you’ve worked with so many publishing houses. Macmillan, Collins, Faber and Faber, Jonathan Cape, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt etc. Did they each serve a distinct purpose?

FD

Again, these publishing houses, some of which I don’t even remember the names of, were the ones which agreed to publish my manuscript attempts through the literary agents I acquired after Macmillan had published three of my young adult fiction books. These brought me to literary occasions and festivals where I made fast friends with the late Jan Needle, a writer who introduced me to his literary agent who took me on.

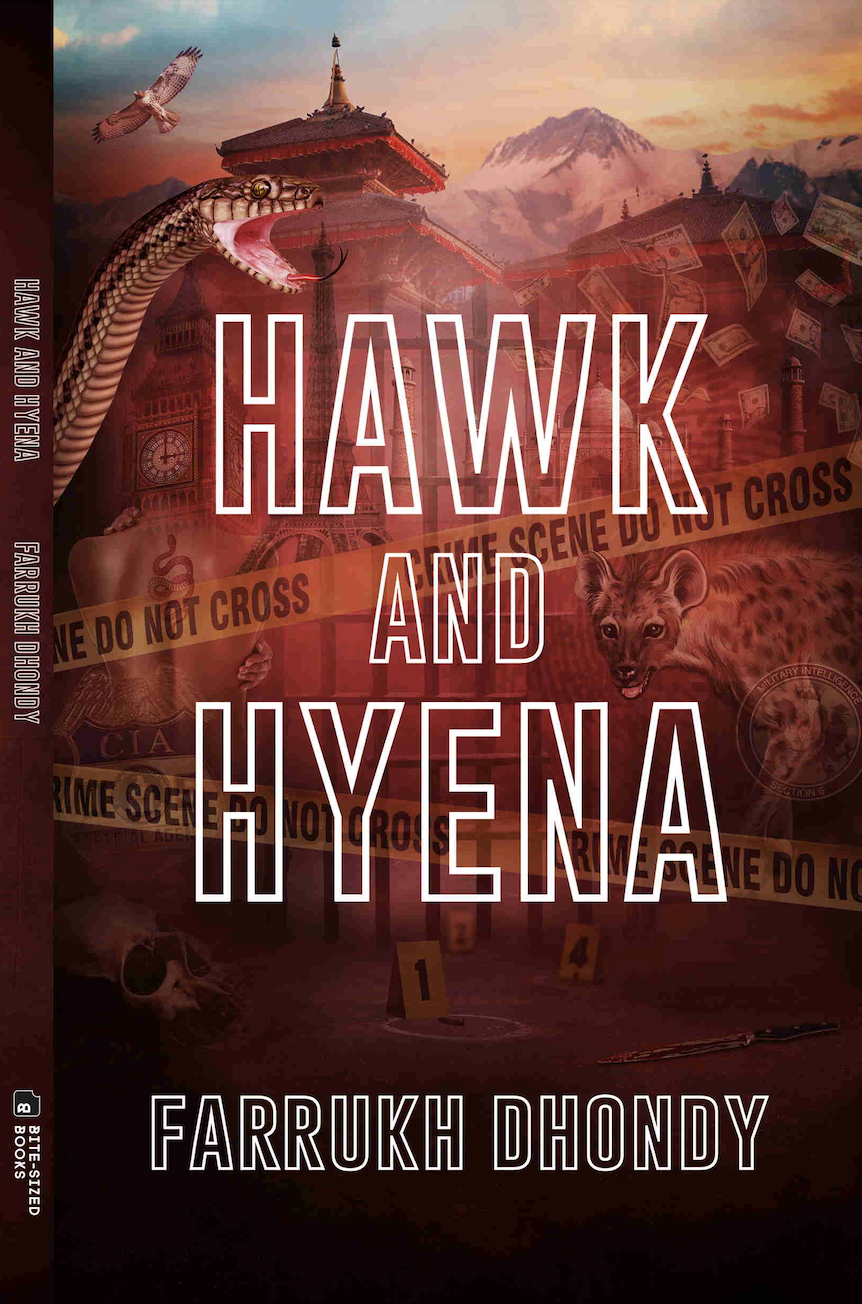

The obvious and distinct purpose the different publishers would serve was determined by the subject matter of what I was writing and its target audience. So, for instance, my first fictionalised account of the life and crimes of Charles Sobhraj was called The Bikini Murders and since he was half-Indian and had just come out of an Indian jail after twenty years inside, he was notorious in India. That was the obvious choice of where to publish.

In later years, since Sobhraj’s contact with me over several years took place almost exclusively in Britain, the obvious publisher, for whom I had written essays on TV politics in anthologies before, was Bite-Size Books. I called the account Hawk and Hyena

Is there one particular work or accolade of which you’re most proud or given you most pleasure? Not necessarily taken from your writings but from all the media in which you’ve been involved. Perhaps even one of your many awards?

FD

That’s like being asked to choose between your children. Yes, I have been given awards for this and that – some awards like “THE OTHER AWARD” for young-adult books which is more obscure than the big prizes. Then there was the Samuel Becket Prize for a single TV play that year, which was given to my play called ROMANCE ROMANCE which I wrote as one of a series of six for the BBC.

Each book or play or series brings its own reactions and rewards and one thing I am proud of is that none of the stagings, broadcasts or publications feels like I have repeated myself or churned out some formulaic product. I wonder if the writers of several books for Mills and Boon can say the same? And does it matter?

JC

TV has played a large part in your career. During your time with Channel Four, you wrote the comedy series Tandoori Nights for the channel, which concerned the rivalry of two curry-house owners. Lots of fun, I’m sure. But you held the important role of Commissioning Editor too. In what way were you able to influence policy and output?

FD

I took the job seriously but not solemnly. It was apparent to me that TV was the central platform enabling and embodying the conversation of the nation. Before my assumption of the responsibility, what was loosely termed ‘multicultural broadcasting’ had been confined to some restrictive categories.

The BBC started with patronising programmes instructing sub-continental viewers to ‘feel at home’ (that was literally the name of one of their first Hindi series) and not to bargain with the person at check-out counters in stores, but to pay what was asked… etc.

Then of course came the casting of blacks as criminals and Asians as clumsy and funny learners of English.

That changed gear when ITV began anti-racist broadcasting with people ranting about ‘racism’ in employment, education, housing, roller-coaster riding…er… I made that last one up! Once the list of areas in which racism was rife was exhausted. the series had to go back to employment, education, housing….

So it was with three determinations that I started my career as a Commissioning Editor. First, that the Mission to Complain was not only boring, it was dead and had to be buried! Secondly that the mission to provide ‘positive images’ was not the job of Channel 4, but rather of advertising agencies such as Saatchi and Saatchi. Truthful images should replace propagandist ‘positive’ ones. And this thing about ‘role models’ which I was harangued by some to provide? My contention was that if role models worked, I would be Mother Superior of a Madras Convent. That’s not to say that children shouldn’t look up to admirable parents or heroes and heroines, but while TV couldn’t provide the first, it could inadvertently provide the second, but mustn’t strain to so do.

And then the third absolute determination was that the lives, cultures, politics, preoccupations and concerns of the ‘multi-ethnic’ Britons, should be exposed through every genre that TV was capable of from current affairs, through drama, soaps, comedy, sport, culturally classical music…keep going…

JC

While at Channel 4 you met Charles Sobhraj, the infamous serial killer, whose life was the subject of the BBC/Netflix series, The Serpent. You’ve had a unique relationship with Sobhraj. How did it come about?

FD

While I was in my office at Channel 4 my secretary rang to say that there was a fellow called Charles Sobhraj on the phone, and he had called several times but wouldn’t say what he wanted or whether he was a producer or director. I of course knew the name, having read two books about his serial killings and was astounded.

“Put him through for God’s sake, Eva!”

She did.

A voice in a heavy French accent came through: “Mr Dhondy, my name is Charles Sobhraj, you might have heard of me.”

“You’re the serial killer,” I said

“You could put it that way,” came the reply.

I asked what he wanted with me. He said, “You were with my cousin Raj Advani in college in Poona”.

I remembered Raj and said I was. “But how is he, your cousin?”

“I’ll tell you when we meet?”

“Meet? I thought you were in jail in Tihar.”

“That’s all over I am in Paris,” he said. And then “Raj says you are the best man in Europe.”

“In many ways I am,” I said, “but best for what?”

“He says you write and have published books. I have my memoirs, and I want you to tell me how to get them published,” says Charles.

Now here I am at a TV channel being offered a serial killer’s memoirs. He immediately said he was bringing the manuscript to me in London the next day.

He did and I introduced him to a distinguished, sprightly mischievous literary agent who was a friend.

JC

And, of course, you recounted that relationship and revealed previously unrevealed facts about him in your book, Hawk and Hyena: What Really Happened to The Serpent. Which you kindly chose Bite-Sized Books to have it published. What are the headlines of what you were able to share in the book?

FD

Though the literary agent concluded that Sobhraj’s memoirs were not in the prose style that any publisher would consider, he also said it was a long boast about how he ‘controlled’ the jails he’d been in and there wasn’t a word of confession or even allusion to his criminal past. So no memoir.

But then Charles kept phoning me for this and that and over the years there were several memorable episodes.

He called late one night saying he was stuck with his ex-wife in a London casino and had run out of money and couldn’t even get his car out of the basement parking – could I come over and give him some cash to get back to France? Did I?

Then there was the time when he approached me with what I considered was an international scoop and I introduced him to the then editor of The Spectator weekly — one Boris Johnson. What happened to the scoop?

And when Afghan terrorists hijacked an Indian Airlines plane and held the passengers hostage, Charles called me to say he could help if I put him in touch with someone in the Indian government as he knew the leader of the hostage-takers. I knew a very senior civil servant – a good friend—and called him. Did Sobhraj’s contact work?

And again, Charles called one day to say “Farrukh, do you know anyone in the CIA?”

“How the flip would I know anyone in the CIA,” I said, but after putting the phone down, it struck me that one of my colleagues at Channel 4 had written a history of the CIA and he could surely put Charles in touch. He did. Why? Why did Charles want contact with the CIA?

Did he involve me in any crimes? No, no murders, but he tried to get me to help him and his partners set up a money-laundering operation for arms sales to terrorists. Did I comply?

All the answers and very many more are in Hawk and Hyena published by Bite-Sized Books.

A final caption in The Serpent serial says “Nobody knows why Sobhraj went to Katmandu risking arrest for two murders” – or words to that effect. Wrong. I know why he went and tell you why in Hawk and Hyena. Tempting?

JC

We shouldn’t forget the lovely book you did with us also; Grannies, Groins and Growing Up. Which is described as: “The experiences in Farrukh Dhondy’s childhood that formed the man who became a best-selling novelist, translator, commissioning editor, historian and playwright are worked into a collection of sonnets that are fun, charming, full of scabrous humour, exciting and above all a real treat to read and savour.”

Presumably intended as the first part of your autobiography?

FD

The autobiography has already been published and is called Fragments Against My Ruin. The Sonnet-form stories of my family memories and my childhood are quite unique, I think, in form and content and I thoroughly enjoyed writing them, sticking to the conceit of using the 14-line sonnet form with its rhyme and metre scheme.

Incidentally my daughters thought the word ‘Groins’ in the title was disgusting, so our next edition should be called “Grannies, Gripes and Growing Up”

JC

You’ve also written, and we’ve published India, My India, a Stab at its History – which is described as; “Farrukh Dhondy brings alive the history of India from its earliest years to its present position as a global powerhouse – with a highly informative, highly readable and personal account of its development – debunking, illustrating, revealing and challenging established views, based on his scholarship and particular insights.” What was the motivation for this?

FD

It started as a sketch of Indian history for my five children who, from their early childhood and later as teenagers and older visited India several times. In their teens and later they went touring or sitting on the beaches, doing God knows what, in Goa or sitting on the bench where Princess Diana was photographed in the gardens of the Taj Mahal. None of them had bothered to find out in any form what formed India from pre-historic days.

I wrote the book originally for them and thought it might work for tourists also. I called it India For Idiots, originally and then thought better of it and renamed it to reflect the fact that it wasn’t a professional historian’s work, but a personal and idiosyncratic attempt. So India, my India – A stab At Its History.

JC

Your political activism is a big part of your life. You initially became involved with the Indian Workers’ Association. What followed, and how have your writings and broadcasting been a platform for your left-wing views?

FD

I’d say that I am not and have never been in my writings a left-wing agitator. Yes, I did write for agitational left-wing papers, such as the Black Panther Movement’s Freedom News and then reports for the magazine Race Today. These were never exhortations but strictly journalism and reviews (in RT under the name of Dread Fred). No agitprop.

The One thing that needs saying is that the fiction and published writing, the stage plays, the TV, even some of the films, were certainly influenced by my political activity. For instance, I worked as a Race Today Collective member in the East End of London setting up vigilante groups of Bangladeshi youths to combat the random victimisation of, mainly defenceless old Asians and families on council estates, which assaults came to be known as ‘Paki-bashing’.

Then one of the main and lasting, significant works we did in the East End was to set up, with an activist called Terry Fitzpatrick, the Bengali Housing Action Group which squatted hundreds of families in streets and estates of the East End around Brick Lane. This experience was used as the background for my four-part BBC drama called King of the Ghetto.

So also the books and stories inevitably draw on my personal experience and observations of black and Asian activity and life. I hope none of these come across as agitprop — though ‘literature’ is a very grand and out-of-reach word.

JC

As usual I like to ask what advice you’d give to an aspiring young or perhaps emerging hopefuls? I’d normally say writer, but your advice may well extend to playwrights, screenwriters, journalists, or any one set on a media career?

FD

I know nothing about genre writing – such as detective novels or Mills and Boon romance. These are very popular and very legitimate forms, but, lucrative though they might be, I have never attempted either genre. I don’t think I could ever write a Game of Clones.

So, my advice for anyone venturing to write fiction or for stage or screen should write from their personal observation of character, speech and events. V S Naipaul once said to me “Why do people go on about my ‘style’? I have no style. I chose the simplest word to describe or say what i mean!”

So, one injunction would be to write ‘window-pane prose’ so the reader looks at the object or thought beyond the words in the sentence. The alternative to be avoided is ‘stained glass prose’ where the writer is inviting the reader to marvel at the words in the sentence which calls attention to itself rather than the meaning it’s trying to convey.

JC

Farrukh, you’ve been a good friend to Bite-Sized Books and a valued personal friend to Paul Davies, our founder and chairman of Bite-Sized Books. Thanks for sharing these personal thoughts.