|

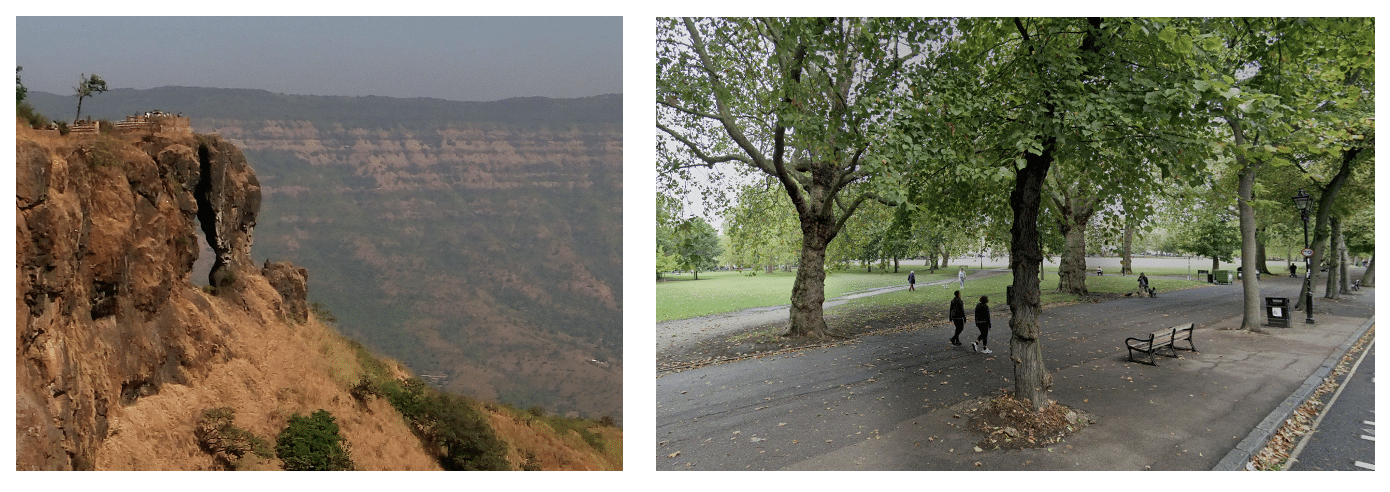

FS – Most definitely. Actually, when deciding on these locations I was playing safe by focussing on places I knew pretty well: Bombay, where I spent my first years but have also visited frequently throughout my life; the hill station, Mahabaleshwar, because it’s one of my favourite spots on earth, a destination for my birth family whenever we wanted to escape the heat of Bombay just before the monsoon rains – and a place that I have continued to visit with my wife, daughter and family; and London (in particular, Islington), which has been my home most of my adult life (although I did spend three years in New York). I have a strong attachment to all these places, but more specifically I felt that writing about them would lend a degree of authenticity that might have been absent if my novel had been set elsewhere.

JC – Without giving anything away, we can say it’s essentially a love story, but what marks it out is the truly unexpected and shocking denouement. Did you have fun structuring the story? How did you go about it?

FS – As I mentioned, I didn’t have anything like a well thought out plan, so to start with there was very little by way of a structure. All I had was the bare bones of what the story might look like – a mystery surrounding something that had happened to a person, the idea for which came from the bizarre occurrence I had read about in the newspaper article. So, if there was a structure, it would probably be true to say that the first thing I knew was the ending (the shocking denouement, based on a similar bizarre occurrence), after which I worked backwards, so that there was a credible narrative arc leading to that final revelation. But, as I said, many of the twists and turns of the plot came to me as I went along – in a way, I was myself discovering what was happening to my characters as the story progressed.

And yes, I had great fun writing the story, partly because, as I said, I enjoy the process of writing, and partly because I was under no pressure from any outside party. I should have made this point earlier, but, when I went to my laptop to start writing, the idea of publishing the final product never entered my head. That happened only much later, when my daughter read one of the first drafts of the novel and suggested that I should think of getting it published.

So, returning to my earlier point, I suppose writing this story was really nothing more than an expression of a creative urge – not dissimilar to singing or painting, for example, activities we enjoy just for their own sake, without any “objective” in mind (we don’t sing in the hope of becoming the next Maria Callas or paint because we want to be the next Rembrandt!).

JC – Are you a disciplined writer? Do you have a word count you want to achieve each day? How many re-writes did you do? Did you write each chapter sequentially?

FS – No, I am certainly not a disciplined writer in terms of going to my laptop at a regular time every morning and setting myself a minimum word count a day. In fact, the whole process of writing was interrupted by large gaps that took me away from the story (but never long enough to discourage me from returning to my computer!). But I think I am more disciplined in another sense – I am one of those people who cannot leave a piece of writing if I find something unsatisfactory about it (it could be something as specific as a word which I feel doesn’t express the exact point I wish to make). I tend to be a perfectionist and can’t bear the thought of producing anything that feels slipshod or substandard.

As a result, I didn’t do that many major re-writes to improve the quality of the language (since I was more or less self-correcting as I went along), although there were important re-writes when I got some truly excellent feedback from my wonderful beta writers. As for the chapter sequence, yes, although the first thing I knew was how the story was going to end I did write the chapters sequentially (I’m not clever enough to want to do something avant garde like writing backwards, leaping back and forth in time or mangling the syntax of basic sentence structure!).

JC – As part of the process of promoting the book, you travelled to India and gave a number of talks, most notably in Bombay at the Cama Institute and the Willingdon Club. I believe you were encouraged to contemplate the book being made into a feature film?

FS – Just as I had no initial plan to get the book itself published, similarly the idea of a screen version of The People We Know didn’t come from me but rather from a number of readers who quite independently told me more or less the same thing – that the book had all the ingredients for a successful screen adaptation: a mystery with a surprise ending (that absolutely nobody has anticipated, to the best of my knowledge so far); the setting in India and London, with a variety of vivid and evocative locations; and an interesting mix of English and Indian characters (the latter from a range of social backgrounds). In addition, I believe this novel combines a number of features missing in most books and screen adaptations featuring Britain and India, past or present: the setting is contemporary, the action takes place both in Britain and in India, and the main protagonist is an Indian woman from whose viewpoint the story unfolds – quite different from, say, A Passage to India, The Jewel in the Crown or The Viceroy’s House (all of which are “colonial” – set in the past, set solely in India and featuring mainly British characters).

JC – What would be your advice to those that would love to write a book, but have no idea where to start?

FS – Just do it! Don’t think too hard, don’t have second thoughts about whether you will be good enough, just enjoy the process and curb your inner critic. Follow the urge, but be true to yourself – don’t let your writing be influenced by what you think will go down well today or by the need to follow some trend. At the same time do seek the feedback of others whose judgement you trust – and that doesn’t necessarily mean joining a creative writing course (I don’t think Shakespeare or Jane Austin did!).

JC – And of course, we all want to know if you’re working on the next book?

FS – I have been mulling over a number of ideas – three quite different ones, to be precise – but I haven’t quite reached the point where I feel ready to put pen to paper. Meanwhile, I have written a short story, both in a long form and in an abridged format, for a couple of literary competitions. Whether or not it does well won’t deter me – who knows, it may even have the makings of a full novel – or indeed a screenplay!

JC – You’ve been kind enough to share the story with me Farrokh and it’s quite intriguing. So good luck with the competition and many thanks for lifting the lid on your life and writing. |