MEET OUR AUTHORS

An occasional series – No.3 Yue He Parkinson

Julian Costley, CEO & publisher at Bite-Sized Books, interviews some of our authors to provide further background to their books and to their approach to writing. And a little ‘behind-the-scenes’ glimpse of their life and influences!

In this, the third of our series; Meet Our Authors, Julian Costley, publisher at Bite-Sized Books, talks to Yue about her former life China and now the UK, her journalist role at Financial Times Chinese, the comparative histories, politics, and culture of the West and China, and her love of cooking (inspired by her friend Ken Hom).

As if she wasn’t busy enough, we here how Yue has switched from the LibDems to Labour and is standing in the July local elections.

YHP – Yes, I’m a columnist for Financial Times Chinese. My life has been really interesting as living in China and the UK has enabled me to compare the massive cultural and political differences between these two countries. I’m really enjoying it. And now I’m on a new journey by standing in local elections, which is helping me to understand even more about British politics.

JC – How did you get into journalism? What did you study?

YHP – Well that goes back many years. I used to host a live TV show in Guangzhou, China, which led to my interest to journalism. And that led to my studying Journalism at a university also in Guangzhou.

JC – You work for FT Chinese based in here in the UK – what brought you here?

YHP – There were a couple reasons. Firstly, I wanted to see the world in the West. There were developments that fascinated me. It was early in the 21st century that China secured entrance to the WTO, and there was the beginning of China’s rise in global influence. Like others, I’d read loads of stuff introducing me to how developed and advanced the West is. I wanted to experience it first-hand.

At the time I’d also received a few of offers from British universities. I chose the University of Bristol and went to study International Relations (IR) in 2004. IR was a popular theme in China then as China had just started to open the door to the world and make friends with the West. I already had set my sights on becoming a TV commentator on IR and this was a job with a future for me because this position favours older people, whereas other TV jobs prefer young and beautiful faces!

JC – You’ve used that know-how and your experience so impressively to publish your first book with us; ‘China and the West: Unravelling 100 Years of Misunderstanding’. What drives this misunderstanding that you have identified?

YHP – The diverse historical paths of course. But on a personal level I’d say I’ve experienced that misunderstanding first hand. My life in the UK has been a challenge because I still have my values from my education In China. Actually, the misunderstanding is not just 100 years in the making, it’s 1,000 years.

JC – Tell us more. Living in the UK and being Chinese must give you a unique perspective. What have you most noticed about British politics, culture and life?

YHP – Wow, it has been an amazing journey for me for these last 20 years living in the UK, as nearly everything here is different, or even opposite, to China. I told many people that I have had to relearn everything in the UK, but I’m fortunate to be amongst the few who have been able to master both the cultures, history and politics. There has been a high mountain between China and the UK which has stopped people understanding each other well, yet, as far as I know, NO ONE has ever written a book about what this MOUNTAIN is. I’m proud to say I’ve done that. China is a seriously unique land, and Western conceptions simply can’t explain China well.

So far my understanding about China, UK and European history and politics is like this: If democracy and dictatorship are necessary in a political cycle, then China is still in the first cycle, which consists of four phases:

1, Feudal System (before BC221), 2, Imperial System (BC221-1911), 3, Democracy (1911-KMT/Chinese Nationalist Party overthrew the Beiyang government and took control of most of China), 4, One-Party System (KMT & CCP brought back the Communist Party model from the USSR -now). In contrast two cycles have occurred on European soil so far. The first cycle, Ancient Greece – the fall of Rome (through democracy to an imperial system). And the second cycle (Christian pope, king co-rule and finally democracy). But in the second cycle in Europe, as the strong force of Christianity was swept away, the moral bottom line and the fear of going to hell was removed, and brutal Nazis and Communists appeared at the beginning of the 20th century. And China was the result of communism supported and nurtured by imported communism from the former Soviet Union. European civilization COULD die as Rome did, and we would enter a third European cycle. It’s not impossible that Europe will eventually be defeated by its own self-inflicted misery; communism.

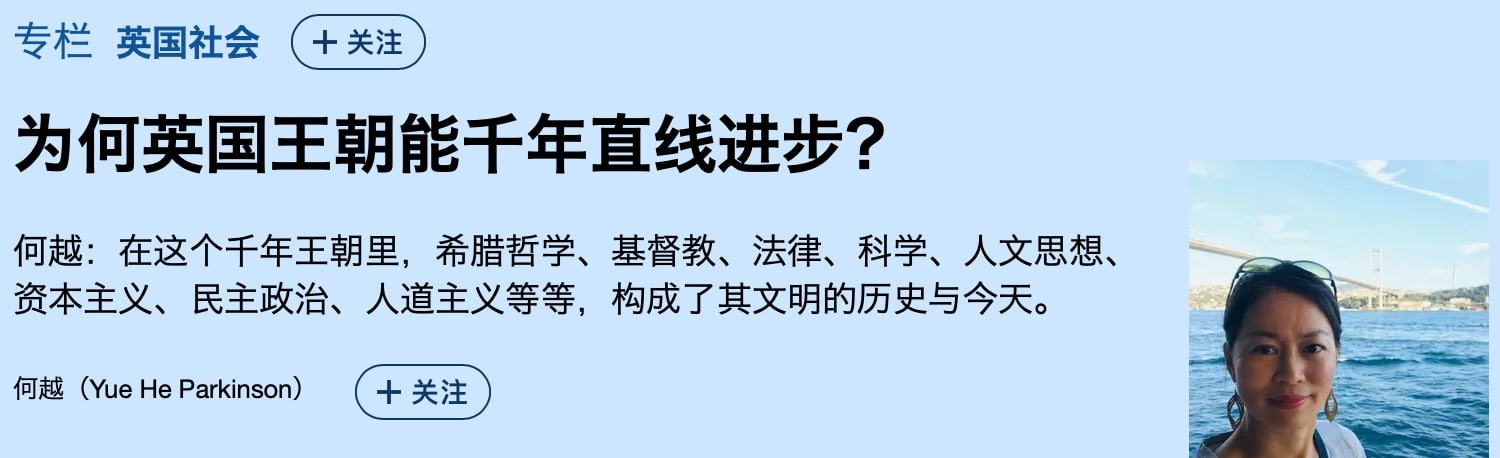

It may of interest for your Bite-Sized Books readers that I did a piece in my column a few months ago which posed the question; Why has the British dynasty progressed in a straight line for a thousand years?

The article is another way for me to answer your question. See: https://www.ftchinese.com/story/001102460. In it I explained British politics and culture via Chinese perspective. Historian Dan Snow was kind enough to comment: “it’s a lovely article’’.

JC – I know you have strong feelings about China’s stance on Ukraine. In your second book ‘China’s Ukraine Dilemma: The shaping of a new world order’ you speak with commendable authority and knowledge – is this a subject you’re passionate about?

YHP – Yes. It’s very shocking for me and many Chinese to witness the competition between China and the US, or may I say – the Chinese government is daring to challenge American hegemony status. My studying of IR laid the foundation for my perspective and scale of observing world order. Two years after my book was published, we can see the world situation has continued downhill, the decoupling of China has undermined globalisation, once a hot theme when I studied IR 20 years ago. Putin is visiting China as I’m writing this – it’s obvious that these two counties are getting closer and are determined to challenge the US and the West.

JC – Turning away from politics and journalism, tell us more of what Yue does outside work. I hear you also have a passion for cooking! And you’ve a close friendship with the renowned chef, Ken Hom. How did you meet?

YHP – Yes, I am extremely lucky to have become a good friend of dearest Ken. He invited my husband and me to his holiday home in south France in 2021 and cooked for us every day! I met Ken 7 years ago in London when I interviewed him for FT China. We both speak Cantonese as Ken’s mum immigrated from Guangzhou to the US in 1948; I came to the UK in 2004, also from Guangzhou.

JC – And we should mention your commitment to the Liberal Democrats. You stood for local council election I believe, and have a close connection to Vice Cable, also a Bite-Sized Books author?

YHP – Yes, I’ll always be indebted to the LibDems for their encouraging me to stand in the local elections in 2023. Also, a huge thanks to Vince who encouraged and supported me to apply for being a PPC (Prospective Parliamentary Candidate). I have known Vince for almost 10 years, and he has helped me to understand British politics from his perspective. I switched to Labour last December, and I am now standing as a Labour candidate in the by-election of Portishead South-Ward Town Council on 11th July.

JC – We always like to ask our authors for advice they would give to aspiring writers and journalists. What would your advice be?

YHP – I don’t feel it’s my place to give advice. I only know I have to read and experience more to write a better book!

JC – A big thank you Yue, and our best wishes for your success in the July elections.

Yue’s books on Amazon:

China and the West – 100 Years of Misunderstanding

China’s Ukraine Dilemma: The Shaping of a New World Order

Yue’s piece in her column

Below is the translation:

As an immigrant from a country where “history repeats itself in a spiral”, it is amazing that British society has continued to progress in a straight line for millennia. The political and cultural differences between these countries, located at the opposite ends of the Eurasian continent, are as far apart as their geographical distance.

Britain has evolved into a fairly benign, egalitarian and fair society, where empire, colonisation and colonial wars are pejorative terms for contemporary Britain, and the Crusades are a tired and archaic feature of antiquity.

From the invasion and conquest of England by William, Duke of Normandy of France in 1066 to the present day, including today’s King Charles III of the United Kingdom, his descendants (both direct and distant) have been the dynastic heirs of the United Kingdom. How is it that Britain’s can move forward in a straight line when millions of dynasties around the world have all collapsed?

Firstly, the competition for the throne is confined to the royal bloodline.

Chen Sheng and Wu Guang’s famous saying, “Anyone can be a King” does not hold true in Britain. That’s because it’s recognised here that ” Only the king’s family can inherit the throne”. The 30-year War of the Roses (1455-1485) was a battle for the throne between the two descendants of King Edward III (reigned 1327-1377), the Lancasters and the Yorks; even William the Conqueror, sounded like he was from France (there was no concept of a country then, and the whole of Europe could be populated by kings of blood at any time. The whole of Europe could be conquered and territories redrawn at any time by descendants of a king’s blood, and there is no period in Chinese history that could correspond to it), but in fact he was also a descendant of Edward the Confessor (1003 – 5 January 1066, Anglo-Saxon monarch of England), when three descendants of Edward the Confessor’s blood (William, Earl of Wessex, and the Viking king Harold III of Norway) vied for the throne, and William was that victor.

Secondly, there were not many peasant revolts in England, and they were not aimed at overthrowing dynasties.

Reading British history with a foundation in Chinese history, it is difficult to understand why peasant revolts were not a common phenomenon in Britain; in the Chinese history I learnt in China, peasant revolts were an important event, often overthrowing dynasties (I wonder if there is a different interpretation of peasant revolts in Chinese history nowadays?). There were not many, but there were peasant revolts in England, such as Wat Tyler’s Peasants’ Revolt in 1381, and the reason for the revolt was that the peasants were oppressed in their livelihoods and were seeking to reduce taxes and end serfdom, not to overthrow the king. The reason was the same as above – ” Only the king’s family can inherit the throne “, and the peasants did not have the heart to overthrow the monarch.

I have recently started attending a Church of England panel discussion organised by our parish priest Rob and his wife. It’s a relaxed format in his home, with tea/coffee and a chat about God. I used to have the impression that Christianity was mostly dark, a tool for priests to fool the people, or a banner for rivalry with Islam. Only recently have I realised that societies within the Christian faith are actually kind and humane, as was the case in medieval times. Those hospitals, schools, religious inns (this one has disappeared), etc. that continue to this day are all products of Christian society. Kings were also expected to do good deeds every day in order to get into heaven. Moreover, at that time, England and Europe were all feudal manor systems, where the king was responsible to the nobles, and the nobles paid taxes to the king; and the king did not have direct contact with the peasants because the bosses of the peasants were the nobles, and the relationship between the nobles and the peasants was underpinned by Christianity, and it was not bad, and might even have been warm-hearted. Such a situation probably resembles the feudal system before the Qin dynasty unified China in 221BC. Chinese textbooks have copied the Marxian view, mistaking Chinese history for a European rehash, and assuming that the China’s Qunxian system, which has lasted to even today since the Qin dynasty was Marx’s European feudal system – which is wrong.

Britain’s involvement in the Crusades and the many colonial wars in its history was between Christian and non-Christian societies, and in these relationships, because they were not governed by Christian “goodness”, evil was allowed to flourish indefinitely. So pre-modern British and Chinese societies were largely the opposite: China was internally evil and externally good; Britain was internally good and externally evil. But after the Second World War Britain’s foreign policy abandoned colonialism and progressed to humanitarianism.

Thirdly, Christianity came first, then the dynasty – there has never been a single strongest political power in England.

Therefore, when William the Conqueror established his dynasty in England in 1066, the fact that Christianity came first and the dynasty came later established a political situation in which the bishop and the king were of kind of equal, the kings of England never reached the heights of power like the Chinese emperors.

Despite the divine right, the Christian archbishops in England did not have the ambition and strength to compete with the king for political rights, and the relationship between the two has survived for thousands of years, and after Henry VIII of the Tudor dynasty changed the state religion to the Church of England, the two still co-exist to this day.

Fourth, two peaceful transfers of power.

In English internal society, political rights underwent two peaceful transfers from the king to the commoners, with the intermediate carrier being the nobility.

1. Compromise between the king and the nobility

The peaceful separation of power between the king and the nobility in England, rather than a major battle, is a rare/rare oddity in Europe. In France, the political rights were transferred from the king to the people through the brutal French Revolution and several republics with their ups and downs. And political rights in the hands of the people of England were transferred from the nobility, not the king. This peaceful transfer and devolution of power was very English.

The relationship between the king and the nobility was not the superior-subordinate relationship of the Chinese concept, but rather similar to a contractual relationship. The Magna Carta, which has been much talked about by many people in China, is regarded as the beginning of the legal constraints that the kings of England had to accept.

Therefore, the kings of England in the Middle Ages were bound by the power of the pope, the nobility and laws, and his power was much smaller than that of the Chinese emperor.

No king would deliberately hand over his power on his own initiative, and the fact that this happened in England is a special background. It happened in the 17th century, when Britain, potentially on the road to a republic, fought the only civil war in history, and King Charles I was defeated and guillotined. But the winning Parliamentarians were unable to maintain their rule after Cromwell’s death and had to take a detour back to the monarchy. By this time Parliament had grown so powerful that it was able to choose the monarch. They expelled King James II and replaced him with Mary II, daughter of James, and her son-in-law, William III, to rule England, Scotland and Ireland, on the condition of signing the Bill of Rights 1689, which was the source of the British constitutional monarchy, known as the Glorious Revolution. And why was William III willing to give up his political rights without resistance? Because he was not an Englishman, but the ruler of the Dutch Republic.

2. The Aristocrats transferred power to the commoners in peace.

The aristocracy ruled England from 1689 until the beginning of the 20th century (when universal suffrage was granted and the right to the House of Lords was largely abolished). This period of history formed the most class-conscious society unique to Britain. But note that even when the aristocracy ruled by privilege, the Prime Minister was elected via a vote in the House of Lords, a democratic vote of the minority. And this political institutional setup eventually extended to a democratic vote for all, with the place of voting shifting from the House of Lords (the House of Peers, which was already a vanity seat) to the House of Commons (the common man), to this day.

In this dynasty, which was opened by William the Conqueror and whose descendants were monarchs for a thousand years, Greek philosophy, Christianity, law, science, humanistic thought, capitalism, democratic politics, humanism, etc., have made up the history and present day of its civilisation, which is reflected in its politics and has led to a straight line of social progress under the rule of the family, which has not yet turned back (as in the case of Rome, where there has been a sudden break in civilisation), If this dynasty is to end in the future, the greatest likelihood is that it will be abandoned by the people in a referendum, ending support for the royal family and leading to its end. The likelihood of a dynastic cycle like the one in China, with violence leading into another dynasty, is slim to none.

And if we have to compare British history with Chinese history, then, as with feudalism, the Chinese feudal system (i.e., before the Qin dynasty 221 BC) was transformed by Emperor Qin Shi Huang into a Junxian (郡县)system, where it was not only impossible for nobles related to the Emperor by blood to share power with him, but also to lose their territories. That Sino-British political divergence went off on a tangent when the Junxian(郡县) system emerged in China in 221 BC. Because of the foundation of Christianity and the separation of powers between the king and the nobles, the king eventually lost out to the nobles and compromised to preserve his status and property but no longer had any power in politics. Even though feudalism in Britain appeared more than 1000 years later than in China, once it did, it did not repeat itself in a spiral, but went all the way up in a straight line.

Unfortunately, the Junxian(郡县) political system invented in Qin dynasty in 221 BC, has lasted to today in China.