POPLULISM

As a politically neutral publishing house, our mission is to bring a wide and balanced range of opinions from our authors to as extensive a readership as we can.

We’ve published many books that explore the politics surrounding the key issues of our time: climate change, the NHS, Brexit, the role and regulation of public service broadcasting, defence policy, housing policy, industrial policy, and of course the government management of the Pandemic.

There’s no denying that we are witnessing a global growth in populism. So given the topicality, we’ve chosen to dedicate this Newsletter to the subject. And to do that we bring you five books that, whether read individually or together, will give you a thoroughly expert briefing and help you form, or even change your views.

So what are we dealing with?

Prominent politicians across the world are directly attacking inconvenient journalists with threats, lawsuits, or worse. They pressure platform companies to remove their work. They belittle and vilify individual reporters when it suits them, often singling out women and minorities. They encourage their supporters to distrust the news, and sometimes incite them to attack journalists.

While depressing, we should not be surprised that this is so.

At its best, independent journalism seeks to hold power to account. When have people in positions of power last liked being held to account? Independent journalists and those in power are not natural friends. They are arguably not meant to be friends. When some journalists sidle up to them, their colleagues, often rightly, criticise the results as toothless access journalism.

When some politicians humoured journalists in the past, it was not out of kindness. It was because they needed them to reach a wide audience. As news media diminish in reach and fewer people trust them, and a growing number of digital media channels and other forms of campaign communication mean politicians and other powerful people no longer need them to the same extent, politicians are no longer so solicitous.

At their worst, political threats to journalism across the world are often part of wider, systematic, sustained efforts to weaken, undermine, or even dismantle the formal and informal institutions of democracy.

PANDERING TO POPULISM? JOURNALISM AND POLITICS IN A POST-TRUTH AGE

This, the most recently published of our POPULISM SERIES, explores the rise of populism and its threat to journalism and democracy.

The book unpacks the global rise of populism and its disruptive effects on democracy and journalism.

Edited by John Mair, Tor Clark, Neil Fowler, Raymond Snoddy and Richard Tait, and co-authored by 39 leading international journalists and academics, the volume offers a timely, in-depth exploration of how populist movements around the world are reshaping political discourse and media practices.

Lead editor John Mair said: “Driven by economic discontent, cultural anxiety and a backlash against perceived elite detachment, populism has gained momentum in many democracies. While often labelled far-right, populist leaders like Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, and Viktor Orbán present diverse ideologies. What unites them is a claim to represent ‘the people’ against entrenched powers, challenging the very foundations of liberal democracy.”

The book highlights how media institutions are struggling to respond. Traditional journalism faces the dual challenge of countering misinformation while resisting the lure of sensationalism. With populists adept at using social media to bypass traditional channels, journalists must navigate a complex environment without compromising ethical standards or public trust.

The authors call for renewed journalistic integrity, emphasising fact-based reporting, diversity of thought and democratic accountability. As the author of the book’s foreword, Sir Trevor Phillips, notes: “Meeting the populist challenge requires not only clear-eyed reporting but also a deeper understanding of the societal forces at play.” This critical volume urges journalists, academics and policymakers to reflect and act, ensuring the media remain a bulwark for democracy in an era of political upheaval.

BUY ON AMAZON HERE

HEALING BROKEN DEMOCRACIES – ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT POPULISM

Author Mark Brolin gives us a brilliantly written parallel analysis.

History proves overwhelmingly that excess dressed up as moderation will, given time, follow any dominant political camp. Mark Brolin describes – while uniquely drawing on key insights from David Goodhart, Matthew Goodwin, Jonathan Haidt, Eric Kaufmann, Daron Acemoglu and Luigi Zingales – why the most recent surge of populism in contemporary politics has evolved as an inevitable counterreaction to Centris dominance and excess.

However, unlike many others who talk about unbridgeable polarisation and dire prospects, Mark maintains that society is already turning a corner.

Mark Brolin is a British-Swedish economist, political analyst and author who regularly contributes to the current affairs debate both in the UK and Sweden. He is a strong believer in realism and political balance rather than in the superiority of any individual ideology. This allows him to present genuinely independent thinking.

BUY ON AMAZON HERE

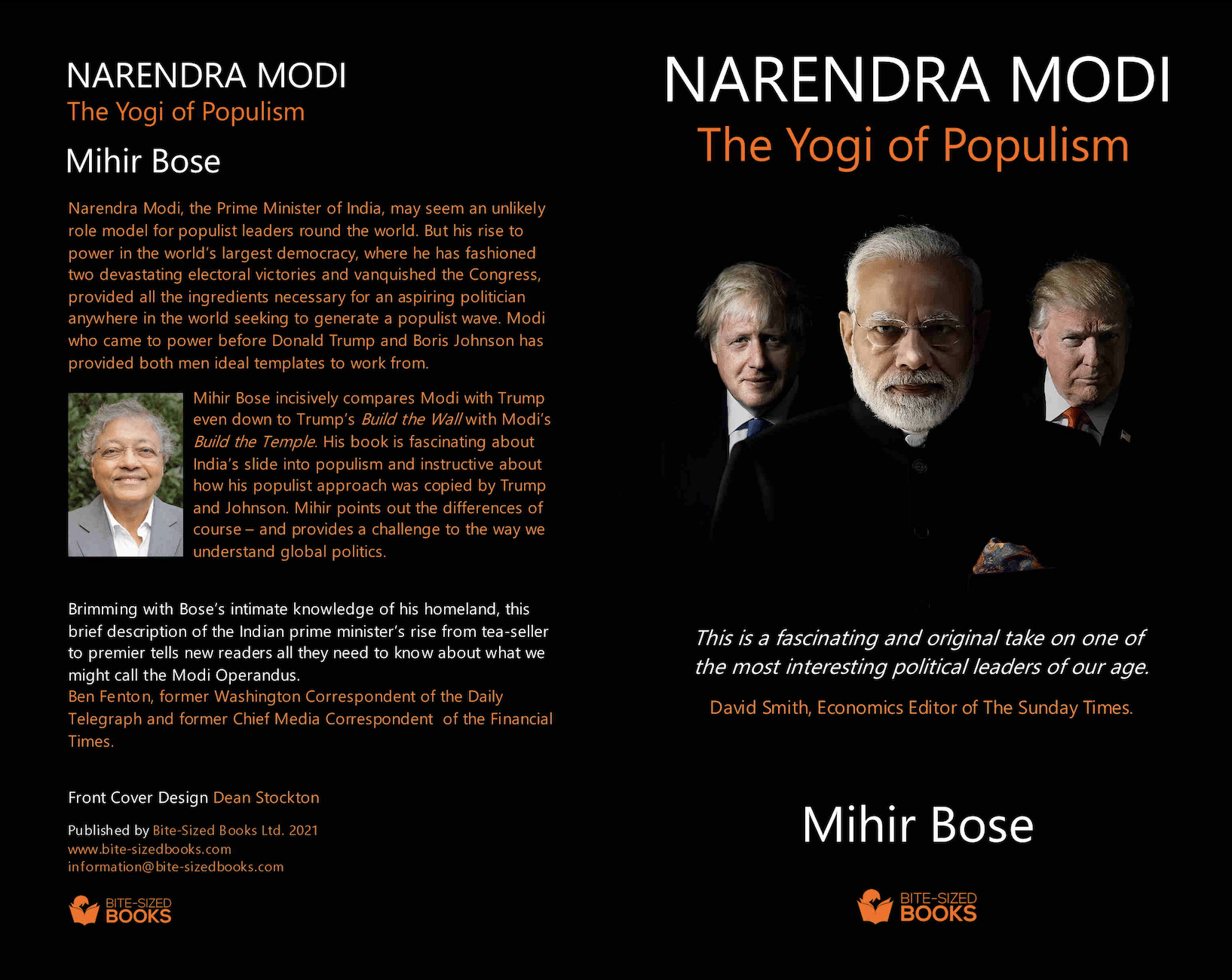

NARENDRA MODI – THE YOGI OF POPULISM

Former BBC editor, Mihir Bose, brings us ‘Narendra Modi – The Yogi of Populism’

Mihir Bose, the former BBC editor and prolific author, explores the idea that India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, provided the model for Boris Johnson and Trump to seize power. And lays out his evidence convincingly.

The notion of Narendra Modi providing the template for Donald Trump and Boris Johnson to seize power may sound absurd. What can the Prime Minister of a developing country, who leads a hard right Hindu party, have to teach two leaders of sophisticated rich countries which pride themselves on being long-established democracies?

India is the world’s largest democracy and Modi’s playbook for winning elections has provided a model for both Trump and Johnson.

The Modi template says to win power you must convince enough people that they have lost their country. That they need to do something very radical if they are to regain their country.

This is such an emotive call that it can galvanise people even when there is no merit whatsoever in the argument. Modi’s success came in the Indian general elections of 2014 which, contrary to the predictions of all the pollsters, and the views of India’s chattering classes, saw his Bharatiya Janata Party sweep to victory with a thumping majority.

This book is an important and challenging analysis that will inform the global political debate and provide real insights into how Trump and Johnson gained power.

David Smith, Economics Editor, Sunday Times quotes, “This is a fascinating and original take on one of the most interesting political leaders of our age”.

Ben Fenton, former Daily Telegraph and Financial Times, “Brimming with Bose’s intimate knowledge of his homeland, this brief description of the Indian prime minister’s rise from tea-seller to premier tells new readers all they need to know about what we might call the Modi Operandus”.

“Bose explains in flowing prose how Narendra Modi exploited dormant anti-secularism among India’s Hindu majority and reversed its multicultural trends. Modi’s brand of populism predates Trump or Brexit or Bolsanaro”.

BUY ON AMAZON HERE

BUY ON AMAZON HERE

Mihir Bose, who was born in India but has lived in the UK for half a century, is an award-winning journalist and author.

He writes and broadcasts on social and historical issues as well as sport for a range of outlets including the BBC, the Financial Times, Evening Standard and Irish Times. He has written more than 30 books and his most recent publication is Lion and Lamb, a Portrait of British Moral Duality. His books range from a look at how India has evolved since Independence, the only narrative history of Bollywood, biographies of Michael Grade, the Indian nationalist Subhas Bose, and a study of the Aga Khans.

Mihir was the BBC’s first Sports Editor, and the first non-white to be a BBC editor. He covered all BBC outlets including the flagship Ten O’clock News, the Today programme, Five Live and the website. He moved to the BBC after 12 years at the Daily Telegraph where he was the chief sports news correspondent but also wrote on other issues including race, immigration, and social and cultural issues. Before that he worked for the Sunday Times for 20 years. He has contributed to nearly all the major UK newspapers and presented programmes for radio and television and has edited several business publications.

Mihir was awarded an honorary doctorate from Loughborough University for his outstanding contribution to journalism and the promotion of equality. He has won several awards: business columnist of the year, sports news reporter of the year, sports story of the year and Silver Jubilee Literary award for his History of Indian Cricket. Mihir lives in west London with his wife.

Mihir is a former chairman of the Reform Club and has recently been appointed to the Blue Plaques selection.

Mihir also has a wonderful podcast series Three Old Hacks with David Smith, Nigel Dudley. Mihir Bose as we’ve listed about is the former BBC Sports Editor, David Smith – Economics Editor of the Sunday Times and political commentator Nigel Dudley have been friends since they first met while working at Financial Weekly in 1980s. They have kept in touch regularly, setting the world to rights over various lunches and dinners. With coronavirus making that impossible, what do journalists do, deprived of long convivial lunches over a bottle of red wine or several?

More about Three Old Hacks HERE

WE DON’T BELIVE YOU – WHY POPULISTS REJECT THE ESTABLISHMENT

Sir John Redwood adds to the debate. Here’s his view.

In many of the world’s democracies traditional parties are on the slide and populist movements are on the rise. I have been charting their ascent and looking at how the establishment tries to fight back in my latest book “We don’t believe you”.

In the USA a populist candidate took over one of the old parties and got into office against all the establishment odds. In the UK the two traditional parties boosted their popularity in the last general election by adopting the mantle of populism by espousing the cause of Brexit, only to wobble by not delivering on time. In Italy two different challenger parties cast aside the ancient regime of the older parties, just as Syriza did in Greece. At the root of much of this is a row over money and tax.

The traditional parties have become wedded to higher taxes to pay for big government. They also impose higher taxes to virtue signal over a wide range of behaviours they want to control, from driving cars and flying away on holiday to eating the wrong foods and buying expensive homes. It took a Trump to sweep in promising to slash individual and company tax rates, cuts which proved popular when he drove them through Congress. In France the Gilets Jaunes protesters took to the streets to demand a reduction in fuel tax, as they were finding it too dear to drive to work or get their children to school by car. Mr Macron tried to turn it into a big conversation with voters, only to discover one of the main demands is lower taxes. Many people think they can make better use of their own money by spending on it on their family and their own priorities instead of the government spending it for them.

The wish to control individual lives has led to taxes on owning a car, buying a car, putting fuel in a car and driving a car. It has led to taxes on buying a home, living in a home, renting out a home and selling a home. It has produced new taxes on foods and drinks the state thinks dangerous, new taxes on rubbish, on plastic bags, on parking, on buy to let properties and much else. It spills over into a wish to control our very thoughts, with a wide range of concerns the subject of surveillance in case people have inappropriate ideas. Taking individually some of these proposals are good. I for one think it right that we ban hate speech, and wish to see less plastic litter around. Taken altogether it becomes too much for many individuals who feel circumscribed, their freedoms damaged, by too many instructions, fees, charges and taxes. Many of the frustrated take to the social media to let off steam. That too is now coming under government control, with new regulations to extend usual media restraints to more private conversations.

In the UK a crucial argument in the Brexit campaign was the wish to take back control of our money. Many voters feel our budget contributions to a rich club of countries is too large. They want that tax revenue to be spent here at home, or given back through lower taxes. At a time when many think our schools and social care could do with some more cash, it seems perverse to send £1bn a month to the EU which we do not get back. Many voters dislike the draft Withdrawal Agreement because it casually gives away a huge and unspecified sum for no good reason. The Treasury thinks it will be at least £39bn. It would probably be considerably more, and stretching forward over many years. EU austerity budgets have done considerable damage to economies and to voter feelings on the continent. The disciplines of the Euro have been stricter than the UK imposed budget rules, and have helped fuel much higher unemployment and falls in real wages which have angered many electors.

The populists are still gaining votes and friends. They offer people hope of a bit more of their own money to spend. They don’t lecture them so much on how they are to live or what they are to think the main problems of the world might be. When the elite come out now with their gloomy forecasts, people often bellow back “We don’t believe you”. The UK establishment came horribly unstuck over its economic forecasts of a recession in the winter after the Brexit vote. All the establishments failed to forecast and prevent the banking crash which went on to cost many their jobs or their businesses. The gap is growing between what the elite say the issues are and what the public wants sorted.

Social media allows the populists to send messages to the many at an affordable price. It allows the public to flag what they want tackled. Many of them want a bit more disposable income, so a bit less tax. They want to be able to get to work or take their children to school by car in an affordable way without too many delays. They want governments to listen to them, not to talk down to them.

Populism is an attempt to get politics to rejoin the public by taking their concerns seriously and trying to do something about them. Many old parties on the continent of Europe are no longer serious challengers for power because they ignored the growing gap between the public and their own views. They now disagree not just on how to tackle problems, but over what problems they need to tackle. Putting prosperity and wider ownership back on the agenda would be welcome for many.

John Redwood is a businessman by background who has led industrial companies and set up an investment management business. An MP since 1987 until 2025, he has been a government Minister and was Head of Margaret Thatcher’s Policy Unit in her middle period in office.

BUY ON AMAZON HERE

INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM TODAY – SPEAKING TRUTH TO POWER

Rumours of the death of investigative journalism have been greatly exaggerated.

This book is proof enough of that. Examples from the corporate and alternative media across the globe highlight the many imaginative and courageous ways that reporters are still “kicking at the right targets”. Edited by – and contributed to – by John Mair and Richard Lance Keeble, the book identifies many of the important trends in investigative journalism, and underlines its increasing importance.

In his Foreword, Peter Taylor, the award-winning reporter, who has been covering terrorism and political violence for 45 years, says of investigative journalism: “It makes headlines, sells newspapers, gets viewing figures and tells the public things they do not know but have a right to know. It speaks truth to power.”

Donal MacIntyre, another award-winning reporter and documentary director, hails the Channel4/Observer Cambridge Analytica probe, in his Afterword, for confronting “the most significant threat to democracy in the last 50 years”.

Brian Winston takes us on a whistle-stop history of investigative journalism from as far back as the fifth century BCE. Rachel Oldroyd argues that if long-term investigative journalism serves the public then the public should be persuaded to pay for it. And Mark Daly tells of his many attempts to get at the truth over the killing of Stephen Lawrence 25 years ago. Finally, in this section, James Oliver, of the BBC’s flagship investigative series, Panorama, highlights the ways in which journalism is rapidly changing. Just a few years ago, leaks would be handed over discreetly in a smoke-filled pub or arrive suddenly in a parcel through the post. Now, you’d need a lorry for the number of documents involved. A big one.

The second section puts the spotlight on international cases. Tatenda Chitagu reports on how a brave tradition of reporting survives – just – in Zimbabwe. Hanna Liubakova shows how journalists in Belarus are finding ways to circumvent censors. Antonio Castillo focuses on Ojo Público (Public Eyes), the Peruvian muckraker, which has revolutionised Latin American investigative journalism. The best-selling Pulitzer Prize-winner, David Cay Johnston, argues that the most important scandals are right in front of the journalists but – for reasons that he explains – they often miss them. And Richard Lance Keeble examines in depth the work of the Australian activist journalist Antony Loewenstein.

BUY ON AMAZON HERE